By Manolo Serapio Jr.

.

About 20 men surrounded their shanty dwelling in Caloocan City one evening in 2016 looking for someone. Failing to find him, the men told Carina*, then 14, and her siblings to go to a neighbour’s house. A series of gunshots soon rang out and when they rushed back home, their father’s lifeless body was sprawled on the floor.

.

Carina’s mother was fatally shot a year later, while playing bingo with friends, by a motorcycle-riding man chasing after someone else. She also lost three siblings in a span of nine years, with one dying in jail and another succumbing to dengue at a young age.

.

To this day, she remembers how minutes after her father was killed, scene of crime officers and funeral workers were at their door, even though they did not seek them out. That no one rushed her mother to a hospital, for fear, that like her father, she too was caught in the Philippine government’s anti-drug war.

The series of horrific, unfortunate events affected her deeply, causing her to be a serial repeater in school. But the coronavirus pandemic brought fresh challenges for Carina. Now in Grade 9, she misses half of her online classes because she shares a single phone with three other cousins also learning remotely.

.

“I try my best, but it’s really tough,” says Carina who lives with her brother’s family, and admits she’ll probably drop out again if school work overwhelms. With her sister-in-law busy with her kids and her brother usually out for menial jobs, Carina mostly has herself to turn to.

.

One of Carina’s teachers called her on the phone, asking why one of her learning modules was incomplete and advised her to stop missing out on classes. “I usually get a special mention in class,” she said.

.

Tougher hurdles

.

More than 2 million students who were enrolled last year skipped school this year amid the pandemic that hit businesses and cut thousands of jobs, data from the Department of Education showed.

.

But as Philippine schools shifted to remote teaching via learning modules and online classes, many students are struggling amid cases of punishing school work and teachers not available for follow-through consultations as well as costly computer gadgets and Internet connection.

.

The hurdles are bigger and tougher for orphans, with no parents to support them and take on the teacher’s role at home, forcing many to work harder to survive and strive for a better future.

.

Yet it underlines the need for communities around them to be more supportive and responsive to their plight.

.

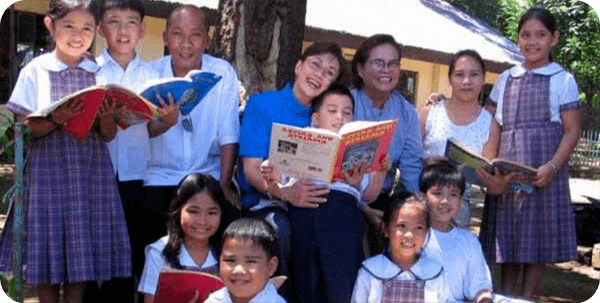

Synergeia Foundation, a non-profit organisation whose vision is for every Filipino child to complete basic education, has been working with local governments across the country to help provide such support to children, including orphans.

.

Synergeia, which has partnerships with organisations like the United Nations Children’s Fund and the U.S. Agency for International Development, has been giving virtual tutorials on subjects like mathematics – streamed live on its Facebook account – to help students cope with the demands of distance learning.

.

The foundation has also been holding online workshops for parents and guardians and writeshops for teachers, and has given nearly 15,000 workbooks to children this year.

.

.

And it encourages small, in-person learning groups led by teachers or volunteers in communities where the risk of COVID-19 exposure is low and where Internet connectivity is weak, with the strictest compliance to health standards.

.

Jane

.

It’s the in-person pre-pandemic school structure that fifteen-year-old Jane* misses, when she can quickly catch up with lessons in class or talk to her teachers. Like Carina, she grapples with her learning modules, opting to leave some questions unanswered.

.

Jane lives in Vigan, about 400 kilometres north of Manila, in a small house she and her brother Gerry* inherited from their parents. They lost their mother four years ago and their father nearly a decade earlier.

.

“Whenever I have a hard time, I cry and I think about my parents,” says Jane whose father died when she was in sixth grade. Her mother was electrocuted at home while the siblings were asleep, and Jane was the first to see her body the next morning.

.

“It was a very painful period in my life, a blow I thought I’d never recover from,” said Jane who’s in Grade 10. They have since been supported by their aunt who lives three villages away.

.

With no phone, computer and Internet, the siblings can’t attend online classes, relying mainly on learning modules dropped off by a teacher neighbour or a classmate.

.

Jane and Gerry are usually up by 6 am, tending to house chores before they begin answering modules covering at least eight subjects that need to be completed every week. They skip meals when deadlines loom, and cook only when hunger kicks in, usually canned food or instant noodles.

.

“It’s hard but I won’t give up. This a challenge I must surmount,” says Jane who aspires to be a doctor. “I know my parents are watching over us that’s why I’m trying to be strong.”

.

Mark

.

Other parentless kids are fortunate to be surrounded by their extended family who look after them.

.

Evelyn* has been raising her grandson Mark*, aged nine, since her son was murdered last year. The suspects are still at large and a case had been filed against them in court.

.

Mark’s mother died two days after he was born, so he only remembers being with his father. “We’ve been honest with him. We told him his father was killed and we don’t know why,” says Evelyn.

.

Now in fourth grade, Mark wants to be a teacher like his older cousin who tutors him after his online classes.

.

“We’re doing all that we can to support him because he’s lost both his parents,” Evelyn says. “He needs to finish his studies so he can make something of himself.”

.

Mark says his favourite subject is English and misses playing on the street, having been cooped up at home for months now like many kids because of COVID-19.

.

His voice was cheery until I asked him what he remembers most about his dad. He paused, then his grandmother told me on the phone that his eyes had welled up with tears.

.

While the void from losing their parents will never be filled, living with their extended families help shield Mark and Carina from harm, keeping their dreams alive.

.

Before her grandmother died two years ago, she wanted Carina to become a doctor someday. “I will try to make her proud, and my parents too,” she says.

.

*Real names were not used to protect their identities