Days after Marawi was sieged by pro-Islamic State militants in May 2017, Omairah Rascal fled the city along with her three young children to a town 17 kilometres away, to escape bullets and bombs that killed hundreds and ruined the capital of Lanao del Sur province.

They stayed in a government evacuation center, but after running out of money for one of her baby’s needs, they returned to her parents in Marawi after a month.

Three years after the five-month battle between Philippine troops and Islamist militants that displaced thousands, many of Marawi’s residents remain in temporary shelters as they deal with the new challenges of the coronavirus pandemic.

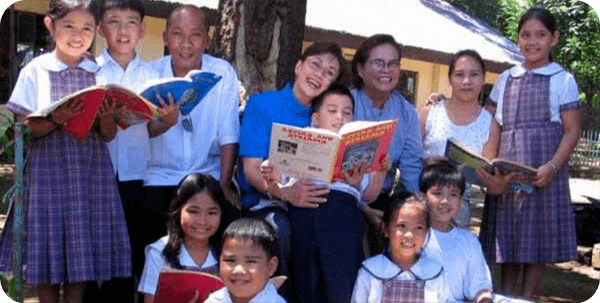

Even before the pandemic, Synergeia Foundation saw a strong need to return Marawi’s children to school, some of whom were cut off from the education system for as long as two years as the trauma from the fighting haunted them. This prompted Synergeia to bring its Adopt-A-Child program in Marawi last year.

As children resume their education through Synergeia’s Adopt-A-Child program, it helps them heal from the wounds of the war, reclaiming a sense of normalcy and stability as they pursue learning in safe spaces that hopefully would reignite their individual aspirations.

Rascal’s eldest child, Johary Haron, only returned to school last year, becoming part of the 163 children in Synergeia’s Adopt-A-Child project in the city.

The program allows anyone to be a foster parent to a child in Marawi by supporting his or her school needs for P600 a month. It’s one of the pioneer programs of Synergeia, an organisation that has been working since 2002 for every Filipino child to complete basic education.

Adopt-A-Child

Along with letters of gratitude, Rascal and other parents whose kids are part of Synergeia’s Adopt-A-Child program, send over a copy of their children’s report cards to the foster parents.

His return to school helped Johary recover in the aftermath of the 2017 siege, says Rascal. But this year presented fresh challenges for the family.

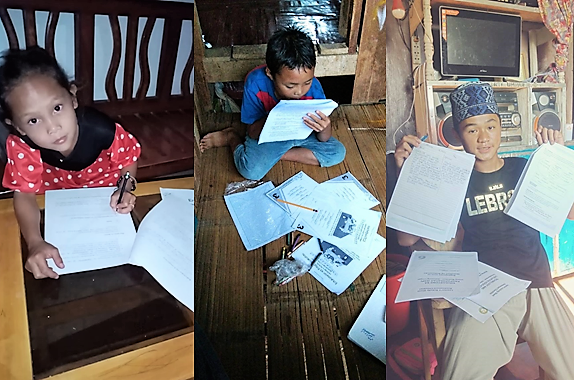

As the health crisis forced schools to close, she had to take over the teacher’s role at home. She divides her time between two of her kids who are on remote learning, helping them out when she can and making sure they liaise with their teachers via call or text if they encounter any issues with their learning modules.

“The teachers here monitor the progress of their students by checking in on them during the assigned schedule for each subject,” she says.

She is thankful that Johary, now in third grade, is able to continue studying through the Adopt-A-Child program. She and her husband barely make ends meet by hawking vegetables, as the pandemic caused her husband to lose his income.

“We are doing everything we can so that our children will be able to finish their studies and won’t experience the hardships that we went through,” she says.

Rascal’s husband was a tricycle driver who ferried students in and out of Mindanao State University. As the pandemic shut schools, it halted her husband’s, and their family’s, only means of income. The bank soon took back their motorcycle after they missed monthly payments, forcing the couple to find another way to feed and raise their children.

In a bid to augment the income of some parents, Synergeia in partnership with the U.S. Agency for International Development, conducted livelihood workshops in June and July to teach them to make hand sanitizers and face masks.

One-woman job

Norma Macot’s 10-year old daughter Jannah who’s in fourth grade and dreams of being a teacher someday, is also part of Synergeia’s Adopt-A-Child program.

Macot is a hands-on mentor to her daughter at home, grateful that she didn’t show any signs of distress after the war.

“Back then, she just wanted to return to school and was so happy when she finally did,” she says. She spent the first allowance she received from Jannah’s foster parent last year on a new bag and shoes to inspire her daughter.

After her husband died in March of a stroke, Macot is getting help from her mother and sister in raising her four kids, two of whom are studying including Jannah’s five-year old sister.

But it’s become a one-woman job for some mothers like Sapia Bayabao who tends to eight kids, a sick husband and a small store.

Of her eight children, six are studying including 14-year old son Amenola who is also in the Adopt-A-Child program and hopes to be a future engineer.

She focuses on her two Grade 6 children, including Amenola, and allows the rest to reach out to their respective teachers when they need to.

“I’d really prefer for face-to-face classes to resume because that will mean a big burden off my chest. But I guess that will have to wait for now,” she said.

By Maricel de Guzman (mdeguzman@www1.synergeia.org.ph)