by Manolo Serapio Jr.

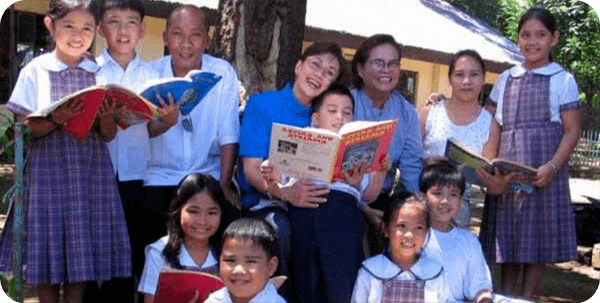

Grade school students, all wearing face masks and seated about a meter apart, lined an area shaded by trees in southern Maguindanao province. It’s Monday and two teachers take turns explaining learning modules that the children are expected to answer for the rest of the week.

The town of Paglat, which hasn’t had a single case of COVID-19 since the pandemic hit the world this year, is among a few places in the Philippines that are taking bold steps to help learners cope with school work through in-person tutorials.

As the pandemic closed schools and transferred learning to homes, many students are grappling with the modules on their own with their parents either working or unschooled and many families unable to afford phones, computer and Internet connection.

Holding in-person teaching sessions, which began in early November, was the idea of Paglat Mayor Abdulkarim Langkuno. He says he was prodded to act by Synergeia Foundation President Milwida Guevara following a virtual meeting with local chief executives of Mindanao just days before.

“She (Guevara) said to think of ways to help the students,” says Langkuno. “I met with all the stakeholders and this is the only solution I could think of to help the teachers, the students and the parents.”

Paglat is among 426 local governments that work with Synergeia, a non-profit organisation whose goal is for every Filipino child to complete basic education.

Even as the health crisis forced schools to shut to curb the spread of COVID-19, Synergeia has continued to engage with educators, parents, students and communities via online workshops and meetings to push for measures and reforms to make sure every child’s education continues unimpeded.

Inspired by Synergeia’s reform push, similar in-person tutorials are happening in other parts of Maguindanao including North Upi, and in Balindong, Lanao del Sur. Other places where similar sessions are being held are San Gabriel, La Union and the towns of Cabatuan and Concepcion in Iloilo province, all done with strict compliance to health protocols.

‘Under the trees’

Like in most of these places, students in Paglat are given tutorials at least once a week. Each session runs for about two hours and covers subject areas in the learning modules provided by the schools that students may be struggling with or need more explaining of.

In some communities, parents are required to bring chairs for their children to limit health risks. Even with no recorded case of COVID-19, residents are still mandated to wear masks and violators are fined.

“The sessions have to be done in well ventilated areas, not in rooms. So most of the time, it’s under the trees, an open-air gymnasium or any open spaces,” said Langkuno.

The local government hired more than 60 additional teacher volunteers – education degree holders who have yet to take licensure examination – to augment the current crop of 40-plus permanent teachers to cover all of its eight barangays.

The municipality, with a population of about 24,000, has nine elementary schools and three high schools.

The open-air learning sessions are a big help for parents in Paglat, where less than 10 percent of adults have finished college, says Langkuno.

‘Best legacy’

Education is close to Langkuno’s heart – it was key to rewriting his life story that in the 1970s was drawn to the armed struggle in Mindanao.

At 17, he was a commander of the Moro National Liberation Front, the Muslim separatist group that fought for an independent Islamic state for decades before reaching a peace deal with the government in 1996.

Convinced by a relative that education should be his priority, Langkuno soon after left his hometown to study civil engineering in Manila. That led to a career in government and later, a big job at the Ministry of Agriculture and Water in Saudi Arabia.

He returned to the Philippines after 15 years, became a lawmaker in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, and was later elected mayor of Paglat, a municipality that was only created in 2001.

“Education is the best legacy,” he says.

Datuan Matu, the school district supervisor in the municipality, says the learning sessions in the purok, or small community areas, are also a more efficient use of teaching resources.

Instead of the teachers making individual house visits, they are able to reach a bigger group of students in a community in one go, giving them more time on the tutorials themselves, he said.

“We saw that the children were able to answer the modules, which means learning is taking place,” said Matu.